Florence, Casa Buonarroti, 24 May – 12 September 2005

Florence, Casa Buonarroti, 24 May – 12 September 2005

In particular, he greatly loved the Marchioness of Pescara, of whose divine spirit he was enamoured, being dearly loved by her in return; he still keeps many letters from her, full of the most honest and gentle affection which would gush from her heart, just as he had written many, many sonnets for her, full of clever contrivances and sweet longing. She often left Viterbo and other places to which she had gone for leisure or to pass the summer, and came to Rome solely for the purpose of seeing Michelangelo.

With these words Ascanio Condivi, in his Vita di Michelagnolo Buonarroti, fulll with information heard "dal vivo oraculo suo" and the publication of which in 1553 was promoted by the Master himself, stressed the centrality of the relationship which evolved between Michelangelo and Vittoria Colonna, Marchioness of Pescara (1492-1547) towards the end of the 1530s and the early 1540s. It coincided with the particularly difficult phase of the artist's development which accompanied the execution of the Last Judgement and the tormented outcome of the lengthy story of the funeral monument for Pope Julius II. It was precisely in the private and intellectual dialogue between the artist and the poetess, both intensely involved in the spiritual anxiety which was shortly to be suffocated by the grip of the Council of Trent, that some of the most extraordinary inventions of sacred subject elaborated by Michelangelo took form.

The exhibition looks into various aspects and evolutions over time of the personality of Vittoria Colonna, in the contexts of artistic and literary culture in which she was active. The exposition therefore starts with a reconstruction of the illustrious Neapolitan Humanistic circle in which Vittoria grew up and was educated, a circle connected with the circuit of courts which linked so many centres all over Italy (Mantua, Milan, Ferrara, Urbino, Venice...), generating a dense and unified circulation of artists and models, both figurative and literary. We will be able to admire the bronze bust of the great philologist Giovanni Pontano, created by Adriano Fiorentino, who came to Naples from the city of the Gonzaga; the medal of Jacopo Sannazaro made by the sculptor and jeweller Girolamo Santacroce, a Neapolitan not without contacts with Mantua; the medal showing the young Vittoria based on the famous model of that made by Gian Cristoforo Romano for Isabella d'Este, precious piece present in the exhibition too. These works eloquently introduce us to the vital world, at once frivolous, sophisticated and oozing with Humanist doctrine, which surrounded Vittoria Colonna in the years before her marriage, celebrated in 1519, to Francesco Ferrante d'Avalos. Moreover, Vittoria Colonna, daughter of Agnesina di Montefeltro, was also the niece of the Dukes of Urbino, Guidubaldo di Montefeltro and Elisabetta Gonzaga, emblematic figures in Baldassarre Castiglione's Cortegiano, the literary masterpiece of that courtly culture in whose lengthy gestation Vittoria was directly involved.

The splendid portrait of Vittoria, painted by Sebastiano del Piombo in the 1520s provides us with an image in which her literary commitment already transpires, and immediately links up with the theme of the privileged relations which bound the Venetian master, friend of Michelangelo, to the circle of protagonists of the religious reform which gravitated around Cardinal Reginald Pole and the Marchioness of Pescara herself. At the end of the third decade of the century, Vittoria Colonna turned to one of Sanzio's pupils when she commissioned from Giovan Francesco Penni, brought to Naples by Vittoria's powerful and dearly loved cousin, Alfonso d'Avalos, a copy of Raphael's Transfiguration which the Marchioness donated to the Naples Ospedale degli Incurabili. We can admire in the exhibition the splendid preparatory drawing, coming from the Louvre. This first section of the exhibition, therefore, brings us up to the wake of the Sack of Rome (1527), when the Castle of Ischia - where numerous literati and Humanists traumatised by the event gathered around the now widowed Vittoria - appeared to Paolo Giovio like a sort of last bastion, tinged with nostalgia, of the enchanted season of the courts.

The early years of the 1530s witnessed the emergence of Vittoria Colonna on the literary scene (already consecrated by Ariosto in Orlando Furioso in 1532), the start of her intense relationship with the figure who was at the time the absolute protagonist of that scene, Pietro Bembo, and the manifestation of her first, irrevocable spiritual anxieties. This was the context within which Vittoria commissioned in parallel two pictures of Mary Magdalen, applying - through the offices of her cousin Alfonso d'Avalos, then General Captain of the Imperial army in Italy - to the two most acclaimed masters of the time: Titian and Michelangelo.

Titian on this occasion produced a penitent Mary Magdalen; Michelangelo, still busily working on behalf of Clement VII on the site of San Lorenzo, created for Vittoria the cartoon of a Noli me tangere, two preparatory drawings for which remain in Casa Buonarroti, with the translation onto panel entrusted to Jacopo Pontormo, pieces all present in the show. The significance which the Marchioness of Pescara attributed to the evangelical figure of Mary Magdalen comes to light also in some of her practical initiatives, such as the foundation in Rome of a refuge for prostitutes.

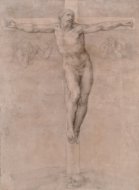

The conclusive section of the exhibition illustrates the season of deep friendship between Vittoria and Michelangelo, documented among other things by the Dialoghi romani in which the young Portuguese, Francisco de Hollanda, gathered the recollections of his Italian sojourn at the end of the 1530s. Here the poetess and the artist figure as interlocutors, brought together by shared poetic interests and by an intense exchange of ideas. This was the period in which Michelangelo conceived for Vittoria three exceptionally famous drawings: the Crucifixion with the live Christ, now lost, but known from the beautiful preparatory drawings coming from the British Museum and the Louvre, all present in the show; the Pietà from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum of Boston, a reflection on the figure of Christ which again connects with one of the crucial aspects of the dialogue between the artist and Vittoria; and the Christ and the Samaritan Woman , of which what has come down to us is a partial study by Michelangelo, while the composition as a whole is known through a print of Nicolas Beatrizet and a painting by Marcello Venusti, both present in the exhibition.

On the strength of the developments achieved through this project over the years, the result of a lengthy research, begun as far back as 1995 in collaboration with the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna, Casa Buonarroti feels certain that the research has yielded what is a truly significant event: an exhibition which successfully brings to life a woman who was a supreme protagonist of her time, whose fame remains linked to her friendship with Michelangelo, but also to the varied and impassioned events which led her from the intellectual worldliness of her youth to become a most striking embodiment of the spiritual and religious unrest of her time.

Casa Buonarroti

Via Ghibellina 70

50122 Firenze

Tel. 055-241752

OPENING HOURS:

9.30-14.

During temporary exhibitions: 9.30-16.

Closed on thursday and on the following holidays: January the 1st, Easter Sunday, May the 1st, August the 15th, December the 25th.